World Environment Day 2025 highlights one of the most pervasive yet often overlooked types of pollution: microplastics. According to the theme “End Plastic Pollution,” this year’s international observance calls on us to acknowledge that small particles of plastic, so minute they go undetected, are entering our food, our drinks, and eventually, our bodies. While the conventional understanding of plastic pollution conjures images of plastic bottles littering beaches or gigantic garbage patches in the ocean, microplastics represent a subtler, but no less dangerous, pollution pathway. This article aims to peel back the layers of this silent threat, examining how microplastics form, how they enter our diets, the health risks they pose, and what each of us can do to minimize exposure.

Defining Microplastics: What Exactly Are We Discussing?

Fundamentally, microplastics are pieces of plastic that are less than five millimeters in diameter, about the size of a sesame seed or smaller. They occur mainly through two channels:

- Primary microplastics: These are created specifically to be small initially, like microbeads in some personal care products, industrial abrasives, or additives in paints and coatings.

- Secondary microplastics: These are the ones that are created when plastic objects larger than microplastics, containers, bags, nets, and packaging, wear away over the years. Ultraviolet (UV) sunlight, mechanical friction (waves, wind, sediment), and chemical breakdown slowly chop up the plastic until it shatters into tiny fragments.

In contrast to organic matter, which quickly breaks down, plastics do not biodegrade. Their compositions, long chains of man-made polymers, remain in the environment, making microplastics build up in land, water, and the atmosphere.

Dr. Sharad Malhotra, Senior Consultant & Director of Gastroenterology at Aakash Healthcare, explains:

“Microplastics are minute plastic particles formed by the decomposition of plastics, which are widespread and hence damage both wildlife and people. They have been found in a variety of foods and can also be inhaled.”

Because they are so small, microplastics often evade conventional filtration systems, whether in water treatment plants or the stomachs of marine creatures, allowing them to travel freely through ecosystems. Over the past decade, scientists have detected these particles in everything from Arctic ice cores to deep-sea sediments, underscoring their ubiquity.

Pathways to the Plate: How Microplastics Enter the Food Chain

Microplastics become part of the human diet through a mosaic of interrelated pathways: from the open sea to our plates. Here, we discuss the major sources and how each forms part of contamination.

Seafood

- Marine Ingestion: Fish, crustaceans, and mollusks tend to confuse microplastics with food. Filters, like those found in clams or mussels, cannot tell plankton from plastic pieces, and as such, microplastic accumulates in the bodies of these creatures.

- Bioaccumulation: When tiny animals are consumed by their larger counterparts, microplastics can be accumulated through the food chain. Plankton consume microplastics; plankton are consumed by small fish, which in turn are eaten by larger fish, and so on. By the time seafood arrives on our plates, particularly top predators such as tuna, cod, or salmon, these particles have traveled through several trophic levels.

- Human Ingestion: When we consume fish (especially whole small fish, shellfish, or while eating fillets in which tissues are not eliminated), microplastics lodged in flesh or trapped in digestive tracts get transferred directly to our body.

Sea Salt

- Ocean Pollution: The World Health Organization estimates that most of the world’s plastics come from coastal countries, spilling into oceans as uncontrolled waste streams. When waves crash, larger plastic pieces are broken mechanically into microplastics.

- Evaporation and Crystallization: When seawater is collected and evaporated to manufacture salt, microplastic particles, which cannot be seen by the naked eye, get included in the crystalline state of sea salt. There have been several reports that have identified hundreds of microplastic particles in a kilogram of commercial sea salt.

Drinking Water (Bottled and Tap)

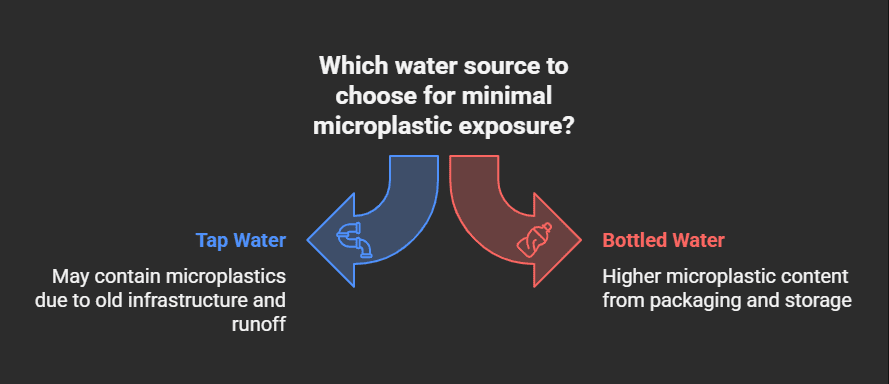

- Tap Water: Even municipal water that has been treated is not immune to microplastic pollution. In areas where water infrastructure is old, corroded pipes, worn-out filtration systems, small plastic fibers from apparel, industrial waste, or stormwater runoff can pass undetected through the treatment system.

- Bottled Water: Ironically, bottled water typically has a higher microplastic content than tap water. Research indicates that the packaging process (manufacture of plastic bottles, filling, capping) and storage conditions (temperature, light exposure) can release microplastic particles directly into the water.

In a 2023 survey by the National Organization for Women, microplastic particles were found in 93% of bottled water brands tested. Additionally, the plastic bottles themselves degrade over time, especially if exposed to high temperatures or sunlight, causing leaching of microplastics into the water inside.

Honey and Sugar

- Agricultural Sources: Sugarcane or sugar beets are commonly planted in areas where irrigation water has microplastics. When plastic-filled water seeps through fields, microplastics may attach to plant surfaces or be absorbed into root systems.

- Processing and Packaging: Plastic-lined containers or plastic filtration equipment can be used in industrial sugar or honey processing. Contact points such as these can be a source of secondary microplastics added during filtration, packaging, or transport.

A 2024 review in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry revealed a mean of 10 to 50 microplastic particles per 100 grams of processed honey and sugar products. While such quantities might appear low, repeated daily intake (e.g., a teaspoonful of sugar per cup of tea, a tablespoonful of honey) equals constant, frequent exposure.

Fruits and Vegetables

- Irrigation Contamination: Wastewater is reused in crop irrigation in most agricultural areas because freshwater resources are limited. Treated wastewater’s microplastic particles may deposit on leaves, bark, or fruits.

- Soil Contamination: With repeated application of plastic mulch and soil additives (for example, plastic-coated fertilizers) for years, soils contain fragments of microplastics. Such particles may stick to root vegetables (e.g., carrots or potatoes) or become absorbed through the root system of leafy greens.

- Post-Harvest Handling: Storage containers, plastic packaging, and plastic mesh bags, common in supply chains, can release microplastics onto produce.

Plastic Packaging (Leaching Due to Storage or Heat)

- Food Storage: Plastic containers, wrap, and single-use packaging have become the norm in kitchens today. When foods, particularly fatty or acidic foods, are put in plastic, the polymers may break down over time, and microplastics are released.

- Microwaving and Heating: Elevated temperatures induce polymer degradation. Upon heating plastic containers (e.g., microwave, leftover food), microplastics and chemicals involved (e.g., bisphenol A, phthalates, or other plasticizers) can directly leach into the food.

Dr. Bir Singh Sehrawat, Program Clinical Director & HOD of Gastroenterology at Marengo Asia Hospitals, Faridabad, notes:

“Microplastics consumed through food, water, or air may build up in the body, particularly within the gastrointestinal tract, raising the risk of certain health issues like gut inflammation, dysbiosis (imbalance in gut microbiota), and potentially increased risk of conditions such as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBS) and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBD). Microplastics may also give rise to systemic inflammation, leading to other chronic conditions.”

By examining all of these routes, we get a sense of how virtually no food group is left behind. While seafood tends to get the brunt of it, thanks to splashy studies of ocean plastics, microplastics have quietly infiltrated processed foods, produce, and even the condiments we sprinkle on daily.

Health Implications: What Occurs When Microplastics Enter the Human Body?

Microplastics do not travel harmlessly through our gastrointestinal tracts. An increasing number of studies identify that they induce a chain reaction of biological effects, some short-term, others long-term, that have the potential to erode our health. Here, we consider the main health issues:

Hormone Disruption

- Chemical Leachates: Numerous plastics have endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) like bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates (widely used to condition plastics), and nonylphenol. In the digestive environment, when the microplastic particles degrade, they are able to release these chemicals.

- Endocrine Interference: EDCs are capable of either duplicating or inhibiting natural hormones. Even trace amounts have been associated with changed thyroid function, reproductive endocrine disruption, and developmental defects in children and fetuses.

- Long-Term Impacts: Chronic low-dose exposure to hormone disruptors has been linked with diseases like early-onset puberty, poor sperm quality among men, endometriosis in females, and metabolic disorders like obesity and diabetes.

Immune System Dysfunction

- Oxidative Stress: When microplastics interact with cells, particularly in the gut lining, they can produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). High levels of ROS cause oxidative stress, which destroys cell membranes, proteins, and DNA.

- Inflammation: Chronic oxidative stress initiates inflammatory processes. Immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages) can try to phagocytose microplastic particles, but since the plastics cannot be metabolized, they can enter immune cells and feed a cycle of inflammation.

- Dysbiosis: The gut microbiome, a bacterial, viral, and fungal ecosystem, is particularly at risk. Microplastics can disrupt the structure and function of the gut microbiota, favoring the development of inflammatory bacteria and inhibiting helpful ones. This imbalance (dysbiosis) has already been implicated in conditions as varied as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) to autoimmune disease.

Dr. Mandeep Singh Malhotra, Senior Oncologist at Art of Healing Cancer, warns:

“Microplastics can also cause DNA damage, leading to cancers. They can interfere with our endocrine systems, that is, the production of hormones. Our immune system also comes under excessive oxidative stress and inflammation, which causes it to dysfunction.”

DNA Damage and Carcinogenesis

Physical Abrasion: Small plastic pieces can physically abrade and irritate the epithelial (cell lining) of the gastrointestinal tract. Tissue irritation over long periods is a recognized risk factor for some cancers, including cancer of the colon.

- Genotoxic Chemicals: Certain microplastics contain additives such as flame retardants, stabilizers, or pigments, many with possible mutagenic effects. As plastics break down, these toxic additives can be leached out and become absorbed into tissues, directly interacting with DNA and causing mutations.

- Carcinogenic Pathways: Experimental evidence (predominantly in vitro or animal models) indicates that microplastic exposure can upregulate cell proliferation genes and downregulate tumor suppressor genes. Though human epidemiological evidence is forthcoming, the mechanistic data provide a credible link between long-term microplastic ingestion and cancer risk.

Respiratory and Cardiovascular Effects (Via Inhalation)

Airborne Microplastics: Microplastics are not isolated to oceans and soil; they have been found in indoor and outdoor air. Sources include microfibers from synthetic textiles (shed during washing), tire wear particles from motor vehicles, and house dust.

- Pulmonary Inflammation: Particles less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5), a subset of the “microplastic” size range, can reach deep into the lungs, inducing inflammation, damage to alveoli, and worsening asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Systemic Spread: There are some studies indicating that inhaled microplastics may translocate from lung alveoli to the circulatory system, where they can become lodged in cardiovascular tissue and cause inflammatory reactions, endothelial dysfunction, and increased risk of atherosclerosis.

Reproductive and Developmental Concerns

- Placental Transfer: In a landmark 2024 study, scientists identified microplastic particles for the first time in human placental tissue. This indicates exposure of fetuses to microplastics in the womb, an issue that raises concerns regarding developmental toxicity.

- Reproductive Toxicity: In animal trials, microplastics have been proven to disable ovarian function, decrease sperm quality, and interfere with sex hormone levels across generations. Even though human evidence is limited at this stage, the precautionary principle requires this evidence to be taken seriously as a cause of concern, particularly for pregnant women, infants, and young children.

Samiksha Kalra, Dietician at Madhukar Rainbow Children Hospital, points out:

Some of the results from microplastic research are concerning. Scientists identified microplastics in human blood for the first time in one study. They identified plastic particles in the placenta of unborn children in another study. Seafood consumers and those working in plastic industry occupations might be at increased risk. In severe instances, long-term exposure has been associated with issues such as respiratory problems, hormonal imbalance, and even organ damage.

Vessel Populations: Who Is at Highest Risk?

Though microplastics are all-nearly everywhere, present in air, water, land, and what we eat, there’s a certain subset that’s exposed at a higher rate or bears more serious brunt.

Beach and Fishing Populations

- Food Intakes: Coastal fishing communities or island nations that consume heavily on seafood intake large amounts of fish and shellfish, which tend to accumulate microplastics.

- Occupational Exposure: Fishermen, aquaculture workers, and those involved in marine tourism are more likely to handle plastic debris and may inhale airborne microplastics near shorelines.

Workers in Plastic-Related Industries

- Manufacturing and Processing: Factory workers making plastic products, plastic recycling plant workers, and workers dealing with plastic raw materials are regularly exposed to high levels of microplastics, and occasionally, to the raw monomers or additives before binding them into stable polymers.

- Health Implications: Chronic exposure to airborne microplastics on repeated inhalation and direct dermal exposure enhances the risk of chronic respiratory disease, skin afflictions, and body-wide chemical leachate toxicity.

People of the City (Especially High-Density Urban Dwellers)

- Air Quality: Highly congested cities with excessive use of synthetic fabric and high traffic volumes create high microplastic pollution through tire wear debris and washing machine wastewater. People of the city, especially those residing in poorly ventilated dwellings, may load up on indoor dust containing microplastics, which they subsequently inhale or ingest through hand-to-mouth activity.

- Water Infrastructure: In certain cities, old pipes and inefficient water treatment plants enable microplastics to pass through into drinking water.

Infants and Young Children

- Dietary Exposure: Infants tend to drink infant formula or breast milk from plastic containers, and as they introduce solid foods, parents might reheat food in plastic containers, further increasing microplastic exposure.

- Physiological Vulnerability: The developing immune system and organs of children cannot detoxify and excrete as efficiently as adults. Ounce for ounce, smaller body mass results in having a greater impact from an equal exposure compared to adults.

Persons with Preexisting GI Diseases

- Sick Gut Barrier: Individuals with diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or chronic gastritis already have weakened gut linings. The presence of microplastics, along with linked oxidative stress, can heighten inflammation and possibly have more serious disease flares.

- Considered as a whole, the populations placed at risk here demonstrate that microplastic pollution is not a ubiquitous, uniformly distributed threat; instead, it amplifies the already existing social and economic risks. For instance, numerous coastal communities have insufficient medical infrastructure to detect or manage emerging microplastic-induced diseases, adding to the public health burden.

The Environmental Side of the Equation: Ecosystem Impacts

To see the complete picture of microplastic pollution, we need to appreciate that human health impacts are inseparable from large-scale ecosystem disturbances. Although this piece is focused on “plate to gut,” a cursory discussion of environmental implications highlights why microplastics are a global crisis.

Marine Life:

- More than 700 species of marine animals have been reported consuming plastics, ranging from plankton to whales. Microplastics ingested by animals may lead to physical obstruction, diminished feeding ability, and starvation.

- Corals and filter-feeding animals like oysters and mussels entrap microplastics in their tissues, undermining development, reproduction, and resistance to climate stressors.

Terrestrial Ecosystems:

- Microplastics settle in landfills, roadsides, and agricultural lands, which can change soil composition, water-holding capacity, and microbial communities that maintain nutrient cycling.

- Earthworms and other terrestrial invertebrates ingest microplastics, which negatively impact their growth rates and survival. The consequences flow up: birds, mammals, and other predators that feed on these invertebrates could experience nutritional deficiencies.

Freshwater Systems:

- Lakes and rivers, most commonly viewed as drinking water sources, have high microplastic loads, originating from urban runoff, wastewater effluent, and agricultural drainage.

- Aquatic flora, fauna, and amphibians in freshwater environments bioaccumulate microplastics, posing threats to biodiversity and possibly influencing livelihoods based on freshwater fisheries and tourism.

By degrading ecosystems and contaminating food webs, microplastics threaten food security for millions who rely on wholesome ecosystems. When the main species collapse or population figures decrease due to pollution, the whole food chain can disintegrate.

Current research: What Science Is Discovering

In the last decade, a tide of scientific research has attempted to quantify and qualify risks from microplastics. Even so, the area of study remains nascent, and there are some notable findings:

Detection in Human Tissues

- In 2022, scientists at the University of Texas found microplastics in human blood plasma for the very first time. The research identified five different kinds of plastic, such as PET (polyethylene terephthalate) and polystyrene, in 80% of healthy blood samples analyzed. This suggests systemic distribution: once consumed or inhaled, microplastics are able to traverse the gut lining or lung epithelium and get into the circulatory system.

- A follow-up 2024 study in Environment International detected microplastic pieces in placentas obtained from healthy pregnancies, raising serious questions about fetal exposure at key windows of development.

Gut Microbiome Disruption

- A seminal study in Nature Microbiology (2023) treated mice with microplastics in drinking water at levels comparable to normal human exposure. After four weeks, the animals had changed the composition of their gut microbiota: SCFA-producing beneficial bacteria decreased, and opportunistic, inflammatory species increased. The outcome was elevated gut permeability (a “leaky gut”), systemic inflammation, and mild hepatic impairment.

- Human pilot studies, albeit small, reflect these results. Volunteers on Mediterranean diets (high in fresh foods) compared to processed diets (greater risk of microplastic contamination) had differences in gut microbiome diversity and inflammation markers, indicating that diet options contribute to the modulation of microplastic-induced dysbiosis.

Respiratory Impacts

- A joint study by the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) traced microplastics in Delhi’s air to various sources: tire abrasion (47%), synthetic textiles (32%), and construction debris (21%). Laboratory tests showed that when human bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to these particles, they produced elevated levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), both key drivers of pulmonary respiratory inflammation.

Role in Carcinogenesis

- Although long-term epidemiological evidence connecting exposure to microplastics and cancer in humans is as yet pending, in vitro studies show that polystyrene microplastics are capable of causing DNA strand breaks in cultured human colon cells. Such DNA damage, if not repaired, can give rise to mutations responsible for malignant transformation.

- In parallel, research on fish and rodent models demonstrates an augmented incidence of colon and liver tumors in high microplastic exposure groups. Though species differences warn against direct extrapolation, these results emphasize the likelihood of microplastic-catalyzed carcinogenesis in humans.

Strategies for Mitigation: What Can Be Done?

No one solution will work to eliminate microplastics from our existence. A solution to this multipronged challenge needs efforts at various levels, individual, community, industry, and policy. In what follows, we lay out practical measures and structural adjustments required to prevent exposure and protect health.

Individual and Household Measures

Select Fresh and Minimally Processed Foods

- Opt for whole fruits and vegetables instead of pre-packaged, ready-to-eat products that tend to arrive in plastic trays or pouches.

- Purchase grains, legumes, and spices in bulk stores where possible, refilling cloth or paper bags rather than buying pre-packaged plastic packets.

- When buying meat and fish, opt for local butchers or fishmongers who use paper (or reusable) wrappings instead of plastic trays.

Switch to Alternative Containers

- Replace plastic lunch boxes, water bottles, and food storage containers with glass, stainless steel, or high-grade silicone options.

- Skip single-use plastic items like ziplock bags; instead, use beeswax wraps or reusable silicone pouches.

- When purchasing household cleaners or personal care items, select brands that provide refill stations (e.g., paper soap pouches, glass bottles).

Skip Heating Food in Plastic

- Don’t ever microwave food in plastic containers, particularly those not specifically marked “microwave-safe.” Heat speeds the degradation of plastic, causing microplastics and chemical additives to directly enter the food.

- If warming up, move food to a glass or ceramic container, cover with a microwave-safe plate or lid, and heat.

Choose Personal Care Products Carefully

- Review ingredient labels on face scrubs, body washes, toothpaste, and sunscreens. See if they contain “polyethylene microspheres,” “polypropylene beads,” or “microbeads”—all signs of primary microplastics.

- Use natural exfoliants (sugar, salt, jojoba beads) or homemade recipes (coffee grounds and coconut oil) instead of store-bought scrubs containing microplastics.

- Choose brands that clearly market “microplastic-free” products.

Filter Your Tap Water

- Install household water filters with the ability to filter particles as small as one micron. No consumer-grade filter is completely ideal, but a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) or reverse osmosis (RO) unit can lower concentrations of microplastics in tap water quite substantially.

- If using bottled water, choose glass-bottled brands when available and store bottles in cool, dark places to minimize leaching.

Reduce Synthetic Textile Loads

- When shopping for clothes, prioritize natural fibers (cotton, linen, wool) over synthetic materials (polyester, nylon, acrylic). During laundry, microplastic fibers shed from synthetic garments contribute substantially to waterborne pollution.

- Invest in a microfiber-catching laundry bag (e.g., Guppyfriend) or washing machine filter that captures microfibers. Wash using gentle cycles, cold temperatures, and shorter wash times to reduce fiber loss.

B. Institutional, Community, and Policy Actions

Improve Waste Management Infrastructure

- Local governments need to invest in state-of-the-art sorting and recycling plants to prevent plastic waste from leaking into natural habitats.

- Compost and organic waste streams must be sorted out from plastic waste at the point of generation. Integrated waste management, recycling, composting, and waste-to-energy, minimizes landfills, where plastics break down into microplastics years later.

Enforce Single-Use Plastics and Microbead Ingredients

- Governments across the globe have started prohibiting microbeads in cosmetics; this should be enforced strongly, with penalties against defaulters.

- Phasing out single-use plastics, e.g., straws, cutlery, plastic bags, and some packaging, has been shown to decrease plastic litter. Initiatives that reward businesses for transitioning to biodegradable or reusable alternatives (e.g., polylactic acid [PLA], paper, bamboo) can speed the switch.

Enhance Industrial Discharge Standards

- Textile factories, plastic factories, and sewage treatment plants must be required to install filters that trap microplastics before effluent flows into rivers or oceans.

- Regular surveillance and open reporting of microplastic content in industrial effluents can ensure accountability of polluters.

Encourage Research and Surveillance Programs

- National health organizations should conduct longitudinal studies to monitor microplastic load in human tissues, blood, and excreta. Surveillance will explain trends in exposure and guide risk assessments.

- Environmental bodies must enlarge monitoring networks, sampling soil, freshwater, marine water, and air, to chart microplastic hotspots. Open data platforms can make this information accessible, enabling citizen science and community participation.

Educate and Empower Consumers

- Education campaigns, through schools, community centers, and digital media, need to make people aware of microplastics, their origins, and the health implications.

- Food companies and retailers can provide transparent labeling (e.g., “plastic-free,” “microplastic-safe”) to enable consumers to make informed decisions.

- Television, radio, and social media public service announcements can reach the public on a wide scale, promoting simple behavior changes: using reusable bags, refusing single-use plastics, and finding alternatives.

Engage in International Cooperation

- Microplastic pollution has no borders, as it is transported by the ocean and the atmosphere. Global standards of achievement, like the Paris Agreement on climate, could establish worldwide goals for lowering plastic output, boosting recycling rates, and reducing plastic leakage into the environment.

- Financing vehicles (such as Green Climate Fund structures) could be leveraged to assist developing nations in the construction of waste handling infrastructure, keeping plastic out of waterways.

India Spotlight: National Context and Response

India’s extensive coastline, enormous population, and fast-expanding industrial bases make the microplastic issue especially acute. Some facts warrant emphasis:

Plastic Production and Consumption

- India is one of the five largest users of plastics in the world, with over 15 million metric tons produced every year. While most plastic products (e.g., single-use bags, packaging) are meant to be used briefly, they remain in the environment for centuries.

Waste Management Gaps

- Whereas cities like Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata enjoy organized waste collection, rural areas depend on waste pickers who salvage what they can and then burn or dump the rest. Open burning gives off toxic microplastics into the atmosphere.

- As per the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), merely 60% of municipal solid waste is collected in India; of this, less than 20% is processed or recycled officially. The remaining plastic, along with it, often ends up in landfills, water bodies, or farms.

Policy Landscape

- The 2016 Plastic Waste Management Rules (PWM Rules) and their amendments added prohibitions on single-use plastics, plastic sticks used for balloons, and items made of thermocol. Enforcement, though, is disparate, with a number of states and local governments hesitant to enforce or track compliance.

- In 2023, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) launched the “Swachh Plastics Challenge,” encouraging entrepreneurs to create scalable solutions for recycling (e.g., chemical recycling, waste-to-energy) and to replace non-biodegradable plastics with compostable ones.

Research and Monitoring

- Institutions such as the Indian Institute of Marine Sciences (IIMS) in Kochi and the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO) in Goa have begun systematic sampling of seawater and sediments for microplastic content. Early findings suggest microplastics in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal exceed concentrations recorded a decade ago by up to 200%.

- A 2024 Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) study detected microplastic fragments in 70% of tap water samples in six large Indian cities: Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru, validating that no part is completely free.

These figures emphasize that microplastic exposure is not just an impending issue; it is an existing reality that touches millions of Indians every day. The intersection of tremendous plastic use, poor waste infrastructure, and low public awareness calls for urgent, concerted action.

Practical Takeaways: How to Shield Yourself and Your Loved Ones

By this point, the dark picture should be obvious: microplastics permeate everything, from crop fields to beaches, from kitchen countertops to our bloodstream. While sweeping systemic transformations are required, individuals don’t have to be helpless. Following is a brief, practical checklist for minimizing personal exposure:

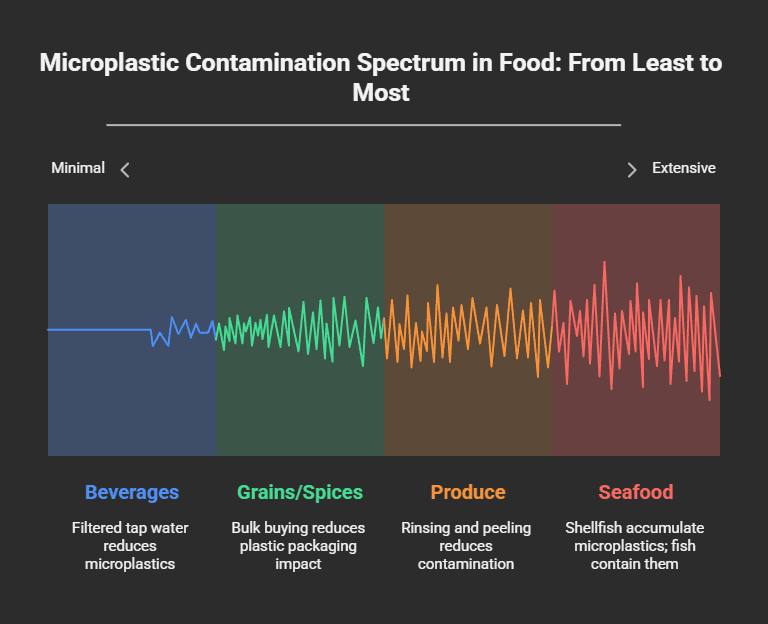

Dietary Choices

- Seafood: Vary protein sources; avoid or limit consumption of filter-feeding shellfish (oysters, mussels, clams) that bioaccumulate microplastics. Gut and rinse fish whenever possible, although some microplastics become lodged in muscle tissue.

- Produce: Rinse produce under running water to remove all visible traces of fruit or vegetable matter. Employ a produce brush to further loosen surface microplastic debris. Peel root crops (carrots, potatoes) whenever possible to minimize surface contamination.

- Grains and Spices: Buy from bulk bins with reusable cloth bags or paper envelopes. Local stores tend to have less plastic packaging than supermarkets.

- Beverages: Filter tap water with a certified RO or activated-carbon filter; for bottled water, opt for glass or aluminum containers. Shun drinks sold in disposable plastic bottles, particularly in warm climates where heat speeds up leaching.

Kitchen Practices

- Storage: Move food from plastic grocery bags or store-bought containers to glass or stainless steel containers with tight-fitting lids. Mark containers with dates to avoid reheating in plastic.

- Cooking: Cook with stainless steel, cast iron, or ceramic pots and pans instead of nonstick pans that usually have Teflon (a type of fluoropolymer). When heating up, put food into a glass bowl and cover with a ceramic plate.

- Cleaning: Select dish sponges or brushes of natural fibers. Synthetic sponges shed microplastics every time they’re washed. Rinse and air-dry sponges thoroughly after washing to prevent bacterial growth.

Home Environment

- Laundry: Wash synthetic fabrics (polyester, nylon) less often. During washing, use shorter cycles, cold water, and reduced spin speed to minimize fiber shedding. Think about using a washing machine filter or a microfiber-catching bag.

- Dust Control: Vacuum carpets and mop hard floors with a damp cloth on a regular basis to trap dust-carrying microplastics. Replace curtains or upholstery, usually packed with synthetic fibers, over time with natural materials.

- Personal Care: Read labels for “microbeads” on shower gels, toothpastes, and exfoliating scrubs. Substitute them with products that have natural exfoliants, bamboo particles, coffee grounds, or oatmeal. Responsible disposal of empty cans is done through flushing them via designated plastic recycling flows.

Lifestyle Habits

- Shopping: Bring your reusable cloth bags; decline plastic packaging on fruits, vegetables, and bulk products. When eating out, request that restaurants to reduce single-use containers and utensils, perhaps by having leftovers put in your stainless steel container.

- Hydration: Use a refillable stainless steel or glass water bottle rather than buying water bottles. Many restaurants and cafes now provide free water refills for customers with their bottled water.

- Awareness: Educate the family members, particularly children, on microplastics. Engage them in discussions on reading product labels, making green choices, and knowing the bigger picture concerning health and the environment.

Advocacy and Community Engagement

- Participate in Local Cleanup Drives: Various NGOs and resident welfare associations hold beach or riverbank cleanup activities. Participating in such activities not only picks up evident plastic trash (which would otherwise degrade into microplastics) but also raises community awareness.

- Support Plastic-Free Businesses: Shop at stores that employ little or no plastic, farmers’ markets, zero-waste shops, and local craftspeople who wrap products in natural materials.

- Policy Action: Contact local representatives to support stronger enforcement of plastic prohibitions, investments in better waste facilities, and public information campaigns focused on avoiding plastic. Sign petitions in favor of extended producer responsibility (EPR) legislation, which requires producers to be responsible for the end-of-life fate of their products.

A Deeper Insight into World Environment Day 2025: “End Plastic Pollution”

World Environment Day (WED), held every year on June 5th, was founded by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in 1974. Every year identifies a focus theme to mobilize worldwide action. In 2025, WED’s “End Plastic Pollution” theme speaks strongly, considering the intensifying manufacture and deep-reaching environmental impact of plastics. Here are some means through which this theme connects directly with the microplastics challenge:

Raising Global Awareness

- On WED 2025, organizations globally, ranging from grassroots NGOs to multinationals, are rallying campaigns to bring plastics’ entire life cycle into focus: production, consumption, disposal, and fragmentation.

- Webinars on education, social media challenges (#PlasticFree30Days, #BeatPlasticPollution), and street activities (pop-up displays tracing plastic waste pathways) all seek to center microplastics in public awareness.

Displaying Policy Innovations

- Various nations are about to introduce new microplastic source bans, including prohibition of man-made glitter (yet another source of microplastics), limiting tire wear particles (through the development of new rubber), and phasing out tiny plastic pellets (nurdles) employed in production.

- The European Union’s forthcoming “Microplastics in Products Regulation” requires that all plastic pellets utilized in industrial activities have to be collected and recycled at rates of over 90%. On Wednesday, policymakers will highlight early achievements in compliance and exchange best practices worldwide

Corporate Commitments

- Large consumer goods manufacturers, from cosmetics and personal care to food and beverages, are laying down timetables for microplastic removal. Brands promise to substitute plastic microbeads used in exfoliants, eliminate unnecessary plastic packaging, and sponsor research into biodegradable alternatives.

- Clothing industry giants are promising investments in laundry effluent filters, with public demonstrations of how pilot projects are making it work.

Community-Level Initiatives

- Indian, Philippine, and Indonesian coastal cities (and others) are introducing local commitments to go plastic-free in markets. Jute or cloth bags replace plastic at street markets; fishermen’s villages promise to rid the waters of “ghost nets” (forgotten fishing nets) that break into microplastics.

- Citizen science initiatives encourage volunteers to take water, air, and soil samples for microplastic testing, creating a feeling of ownership and direct participation in a scientific endeavor.

By connecting local initiatives, like replacing single-use cutlery with bamboo, in isolated villages, to global conversations around circular economy systems, WED 2025 emphasizes that it will take a worldwide system of solutions to end plastic pollution: creative technologies, enabling policies, and grassroots activism.

Looking Ahead: The Road to a Plastic-Resilient Future

To remove microplastics from our ecosystem is a challenging undertaking, considering that several hundred million tons of plastic have already been manufactured, and only a small portion of this has been recycled. However, the story does not necessarily have to be one of gloom and despair. A confluence of technological advancements, governmental legislation, and evolving public awareness provides an avenue of hope.

Technological Innovations

Advanced Filtration Systems:

- Scientists are creating nanofiber filters for sewage treatment plants that can trap particles measuring 0.1 microns in size, preventing most microplastics from entering rivers and oceans.

- Household water faucet point-of-use filters are being engineered for domestic home taps so households can filter microplastics out of their drinking water at home.

Biodegradable Plastics and Circular Polymers

- New materials, like polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are based on bacterial fermentation, hold the potential for biodegradable plastics that break down into harmless biomolecules naturally.

- Advanced chemistry recycling methods can depolymerize plastics into monomers, allowing complete circularity. These processes, although energy-intensive at present, have potential for future cost diminution as technology develops.

Bioremediation:

- Some fungi and bacteria (such as Ideonella sakaiensis or certain fungal species) can degrade plastics into their constituent compounds. Pilot programs are investigating the potential of using these microorganisms, either through composting heaps or specialized bioreactors, to address environmental microplastic pollution.

Policy and Governance

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR):

- Policy that requires manufacturers to reclaim, recycle, or dispose of products at the end-of-life force industry players to design with circularity. Including disposal costs in the calculation, businesses are motivated to reduce the use of plastics and invest in substitutes.

National Action Plans:

Plastic action plans have also been implemented by countries like Canada, Rwanda, and Costa Rica with detailed targets to decrease single-use plastics, improve recycling, and fund waste management. India is going to introduce its upcoming National Plastic Action Plan (NPAP 2.0) with more advanced provisions than the previous PWM Rules, including microplastic-specific features like standardizing microfiber filters in washing machines.

International Cooperation:

- Negotiations at the UN Environment Assembly are ongoing for a worldwide treaty on plastic pollution, to establish binding reduction goals, common definitions (e.g., what constitutes a microplastic), and funding for waste management in poorer nations. A draft treaty by late 2025 could represent the first internationally legally binding global system of its sort.

Public Engagement and Behavior Change

Educational Curricula:

- Incorporating modules on microplastics into school curricula, from elementary to university levels, will ensure a generation of people growing up with an acute understanding of the lifecycle of plastic and its impacts. Hands-on learning activities (like microplastic sampling in nearby water bodies) develop scientific literacy and environmental responsibility.

Media Campaigns and Citizen Science:

- Documentaries (like “Invisible Menace: The Rise of Microplastics”) and social media influencers who promote zero-waste living help raise the alarm on mitigating microplastic pollution.

- Volunteer science websites, where citizens upload microplastic samples from their community, provide huge, open-data repositories that scientists can sift through to detect pollution hotspots.

Cultural Changes:

- Aside from personal decisions, social norms must change. As smoking in public places became de-normalized over a matter of decades, so too must thoughtless plastic consumption. When saying no to a plastic straw or using a reusable bag comes to be seen as something everyone does, as a social norm, rather than as an added exertion, behavioral modification speeds up.

Conclusion: A Collective Responsibility

Microplastics are the ultimate “wicked problem.” They are the product of modern convenience, single-use items, plastic packaging, and synthetic clothing, yet they haunt the ecosystems upon which we depend and threaten both human and environmental health. By 2025, the scientific world will have come up with strong evidence that these particles do not move through our bodies inertly; instead, they come into contact with cells, tissues, and biological systems and leave behind traces in our blood, our placentas, and even our lungs.

World Environment Day’s 2025 theme, “End Plastic Pollution,” couldn’t be more apt. This year’s appeal is not about beach cleanups or plastic bag bans but requires a fundamental overhaul of how societies manufacture, use, and dispose of plastics. The transformation from “plate to gut” points out that microplastics are not a future menace but a pressing individual and intergenerational issue.

Every individual has a role to play: choosing fresh foods, replacing plastic containers with glass or stainless steel, and reading labels to avoid microbeads. Communities must pressure local officials to improve waste management, and industries must innovate toward a truly circular economy. Governments need to enact and enforce tighter controls such that the onus of plastic waste does not rest increasingly on the weakest shoulders: coastal villages, poor families, and unborn generations to come.

The path to follow is difficult, but the cost of failure is too great. Inaction risks sealing microplastics into a permanent place in the human condition, something transmitted from parent to child, generation to generation. In embracing the 2025 spirit of World Environment Day, however, we can decide otherwise: a future in which plastic pollution of every sort, its visible presence in some places, its invisible spread in others, is something left behind, not something handed to tomorrow.